When the Coat of Hopes visited Eastbourne

By Sam Powell

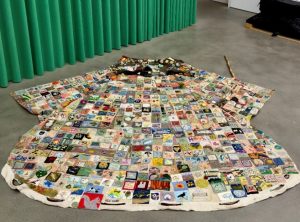

In late September 2025, the widely acclaimed magnificent Coat of Hopes stopped for a meet and greet at the Towner Eastbourne on its way back to Newhaven, where its journey began four years ago.

For the 2021 COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference, with 120 world leaders in attendance, Barbara Keal (pictured below), the artist creator of the Coat of Hopes, walked with others all the way to Glasgow, Scotland, in an impressive 9-week pilgrimage.

Barbara Keal

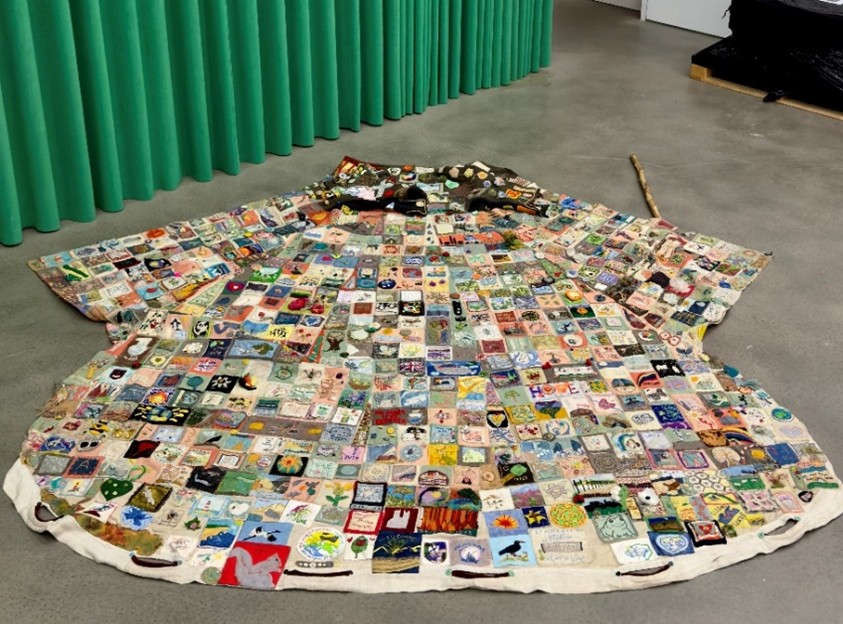

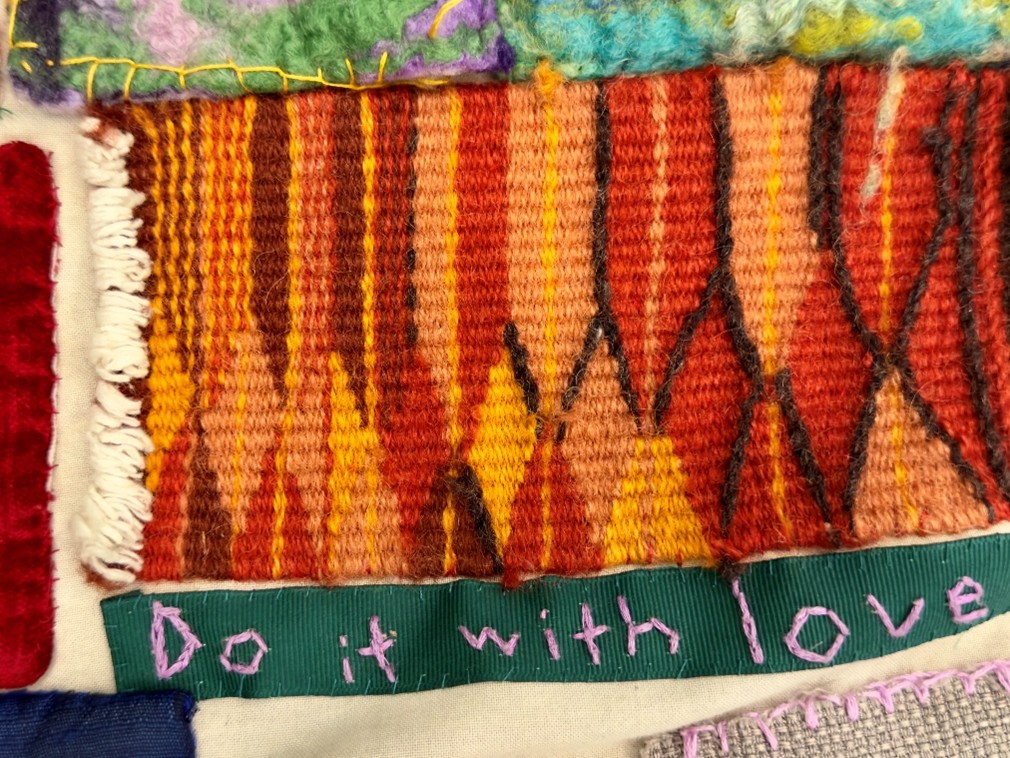

The Coat started as a bare up-cycled army coat, and collected patches of hope sewn into it as it went, from each location it visited. Each patch looks different and generally holds an environmental message and/or the place names. The first patch was sewn in Newhaven.

A moving artwork

Anyone who meets The Coat can try it on to feel “the weight of the Coat”, like this lady below. As is shown below, the Coat also has a song that is sung to those who wear it.

As Barbara says, it is a moving piece of collective art: “to warm you with a sense of what to do, to carry your voice. Only by many hands can such a coat be made, stitched, and joined on a journey, like a living fable, travelling on many backs.”

This poetic central message was echoed by Tom, one of the members of the small group walking with Barbara on this leg from Hastings (walk 28). “It’s not a work of art to be looked at and consumed. It’s about participating in this.” For him, the type of hope The Coat is carrying is a verb, something we have to do, to “dream into being”, envision and “step towards”.

Barbara and The Coat’s carriers also acknowledge the challenges of this collective work. Entering unfamiliar spaces and meeting people with different views can be uncomfortable, she said, but that discomfort is part of the process. “We all belong together, that’s the only way to face a problem of this scale. When you say, ‘we are not with you,’ you start to build conflict.”

The Coat is a living archive, unfinished, evolving, and collaborative – a space of openness and reflection. Asking one of the walkers if they thought there would ever be an end to the Coat, she told me, “It is still being made.”

Many feet and its song

After the Towner on Friday, the walkers travelled from Eastbourne to Alfriston on the Saturday. I met them to walk to Newhaven on the Sunday morning.

Singing accompanies The Coat on its journey (with the first verse location name and its journey location changing depending on place), marking its arrival and departure from a location and various points on the journey when The Coat is worn by someone new.

(Chorus)

Ask me where I’m going

Ask me what is my purpose

Ask me what my name is

They call me the Coat of Hopes

(Verse 1)

To Newhaven today to stay till Westward I’ll be bound

Worn and walked along my way when those willing can be found

In truth, my destination is each person that I meet

The turning of our future is on all our backs and feet

(Chorus)

(Verse 2)

What is it that I’m taking to the ones who will decide

If as a world we’ll do all in our power to survive

Only pieces of blanket I’ve collected on my path

With grief, hopes, prayers, remembrances for the lands through which I’ve passed

(Chorus)

(Verse 3)

So here’s my invitation, come and make me who I’ll be

Mark your hopes on blanket and I’ll sew them into me

A coat that’s made by everyone for everyone to wear

To feel my warmth and the weight of responsibility we share

(Chorus)

Naturally, we were met with inquisitiveness and a wide array of emotions. Dog walkers, children at a skatepark, people driving to work, stopping and coming over, and passers-by all turned an eye, and were welcomed and invited to try on The Coat if they wished. Some were almost brought to tears when wearing it, illustrating its meaningful agency.

The mayors of both Newhaven and Seaford came to see it. In Seaford, roughly 30 people attended a picnic on the beach, and there was a welcome event hosted by the Seaford Environmental Alliance.

Many from Seaford also walked with us to Newhaven, where others were awaiting The Coat.

After travelling 1906 miles, The Coat of Hopes had finally arrived back in Newhaven on 21st September. It was greeted gloriously by the Ouse Valley Morris dancers.

The next journeys

On Sunday, 9th November, The Coat left again (walk 29) to go to a COP30 rally and march in Brighton on the 15th November. It was on display temporarily at the Dorset Gardens Methodist Church.

Barbara said there are plans to go West in the new year: “At the beginning of next year, we’ll set off for Land’s End. We’ve been to the most easterly point — now we’ll walk to the most westerly. There are lots of journeys within journeys.”