One of the things I love about living in Eastbourne is access straight up onto the South Downs. I enjoy walking on the Downs, taking in the views, especially those that look out to sea, but one of the most enjoyable aspects for me is the chalk grassland. Chalk grasslands are found in northwest Europe, and are some of the most species rich habitats we have, in fact they have even been called the European equivalent to tropical rainforests because they are so species rich. They are particularly rich in plants with up to 45 different species in one square metre on the best sites. You can find many species of orchids, wild thyme and other herbs, tiny eye-brights, milkworts, and fairy flax, bold knap-weeds, and fine grasses as well as the County flower the blue and spikey round-headed rampion. They are also known for their invertebrates, with numerous species beetle, butterfly, moth and grasshopper found exclusively on chalk grasslands.

You would be forgiven for thinking that as we live at the foot of the South Downs – a chalk ridge that runs all the way to Winchester in Hampshire – and that for the most part in the open landscape of the eastern end of the Downs, that chalk grassland is the dominant habitat. Unfortunately like many other habitats in England our abysmal lost of biodiversity has reduced the amount of chalk grassland across the South Downs to just 4 % of its original cover. But before digging into why we have so little left, lets get into what exactly chalk grasslands are.

Chalk grasslands are often referred to as calcareous grasslands. This is a fancier way of saying something is rich in calcium carbonate. In this case it is the chalk bedrock under the soil. However, this is really important as it affects the pH of the soil. That scale of acid to alkaline. And because the bedrock of the South Downs is chalk, the soils here are alkaline. It is worth pointing out that another feature of these soils is that they are generally shallow and very nutrient poor. Sometimes the plants that grow on places like the South Downs are referred to as calcicoles. A calcicole is a botanical word which simply means a chalk loving plant. So, the chalk grasslands on the South Downs are a suit of plants adapted to the alkaline soils which overlay the chalk bedrock, many of which are restricted to growing only in places where chalk or limestone underlay the soil. And despite what may sound contrary, these plants thrive on the thin nutrient poor soils, indeed it is these very conditions that make chalk grasslands so species rich because it stimulates competition between species.

But why is there so little of it, and what is growing on the South Downs if it’s not chalk grassland? There used to be far more chalk grassland on the Downs than there is now and that is due to former land use. Some form of management is required to maintain chalk grasslands. Livestock grazing, on the higher and steeper slopes, especially with sheep is the traditional use of the South Downs. Sheep grazing has been active on much of the Downs since before the Roman times, but was dominant from the medieval period onwards until World War II. The soils on the Downs are shallow and nutrient poor, and often dry because rainwater percolates away quickly through chalk. Conditions that meant that until more recently this land was unsuitable for arable (crop) production, which was confined to the foot of the Downs, although some of the south facing more gentle slopes have been ploughed since the 1700’s. Post-World War II saw the advancement of technology in agriculture through machinery, biocides, fertilizers and resistant crop strains which lead to land that had previously been considered unsuitable for crop production being ploughed up on the South Downs. This greatly affected the way the South Downs were farmed; with only the steepest slopes left unploughed.

The reality is that most of it has been lost. What remains of good quality chalk grassland on the South Downs make up less than 30% of the calcareous grassland in the whole of the southeast of England- other areas include the Surrey Hills and the Kent Downs. Most areas of chalk grassland are confined almost exclusively to highly fragmented patches on the steep north facing slopes called the scarp slope. This becomes really evident if you ever look at the location of protected sites known as Sites of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI’s) across the eastern half of the Downs. They are predominately found on the northern facing slopes. Fragmentation, or the breaking up of large areas of chalk grassland into smaller isolated patches leads to the rapid loss of calcicole plant species from remaining chalk grassland, and associated invertebrates. The good news was that the steeper slopes provided an environment more resistant to change for chalk grasslands, because the soil can be especially thin on these slopes, which in turn favours the calcicole species. However, farming practices are continuing to change, a new problem has arisen as the steeper slopes are abandoned from livestock grazing or indeed any management at all, which has led to the encroachment of scrub and ‘secondary’ woodland. This smothers the grassland and has meant the gradual loss of calcareous grassland on even these steeper north facing slopes as well.

Restoration of chalk grassland often involves the removal of scrub, trees and shrubs and the reintroduction of grazing to maintain its characteristic short grass. If an area can’t be grazed then it can be cut, although the cuttings need to be removed, this is because as cuttings rot down, they return nutrients to the soil and this allows plant species that we wouldn’t normally see gain a foothold into these plant communities, such as nettles. The little calcicoles cannot compete with the likes of quick growing and tall nettles and soon disappear.

Eastbourne is no exception in having lost some of the steep scarp slope to secondary woodland, which more recently has been devastated by ash die-back disease. However, we are also fortunate in Eastbourne as we do still have some really good south facing chalk grassland particularly between Holywell and Cow Gap.

Fortunately chalk grassland is now designated a ‘priority habitat’. This means it is a habitat that has been identified as threatened with loss and requiring conservation action, something that the South Downs National Park is working hard on. There is another important grassland on the chalk slopes around Eastbourne, known as good quality ‘semi-improved grassland’. Good quality semi-improved grassland is the grassland best placed for restoration to chalk grassland, as it contains many of the calcicole species. But what sets it apart from chalk grassland is that it is likely to have been victim to agricultural ‘improvement’ at some point, or other poor management from which it is now recovering from.

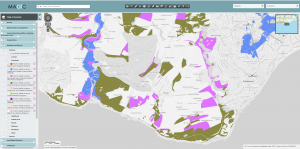

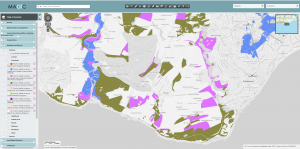

If you want to see exactly where chalk and semi-improved grasslands can be found in and around Eastbourne, it is worth first looking at Defra’s Magic Map Application (defra.gov.uk), an open resource that maps all of England’s designated protected sites and areas as well as priority habitats. Below is a snapshot to illustrate all of the priority grasslands found in and around Eastbourne.

I couldn’t write this blog without talking about carbon, because this is the Eastbourne EcoAction website right? Well chalk grassland (and indeed all other species rich grasslands) are a huge source of carbon stores in their soils. In fact, carbon stores in grassland soils are, in some cases are as good as the stores in woodland soils. However, disturbance of the soil, such as ploughing or digging up releases that stored carbon back into the atmosphere and it can take a long-time to restore what has been lost. We also now know that the more species diverse grasslands hold more carbon that species poor grasslands – another great reason to love chalk grasslands, and see them being restored.There are four priority grassland habitats: calcareous grassland (khaki), coastal and floodplain grazing marsh (blue), lowland meadow (lime), and good quality semi-improved grasslands (purple). The map shows how lucky we are to have so much south facing chalk grassland, a rarity indeed. Likewise, we can see how much of the scarp slope facing Eastbourne is good quality semi-improved grassland, ideal for restoration to chalk grassland.

So, although much has been lost, chalk grassland is recognised as one of the most biodiverse habitats we have in this country, and here in Eastbourne have it on our doorstep – our own rainforest in miniature! Restoration projects help enhance and restore it to its former glory and that in turn supports a host of other species, many of which are also in decline that are dependant on it. So next time you are out on the Downs, I encourage you to try and find some of the places the chalk and semi-improved grassland exists, take or download a plant I.D. guide and see what you can find.

Author: Sarah Brotherton is an ecologist who lives in Eastbourne, currently working for the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.